I didn’t want to hi-jack a war movie thread about Japan bombing the United States. So I started this one. More than a few years ago, my daughter and I visited the National Air and Space Museum (Stephen F. Udvar - Hazy Center -- Near Dulles Airport -- there is bus service from Dulles Airport -- beats the $16 parking fee). We went on the docent volunteer tour (its free). The docent stopped by this airplane, that sits next to the Enola Gay.

https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/aichi-m6a1-seiran-clear-sky-storm/nasm_A19630308000

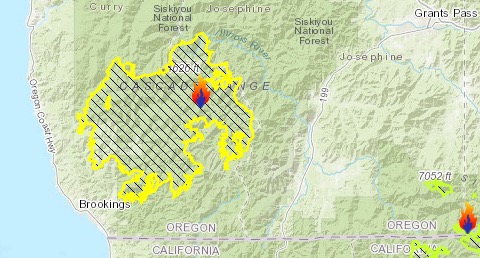

The story goes: The actual Japanese pilot of the plane ( this had to be like 4th hand) saw this airplane at the Air and Space Museum and said the Enola Gay saved his life, there was a mission where a Japanese submarine armed with 2 of these airplanes sealed in a watertight bay would make its way to the United States eastern coast, where the 2 planes would launch, one would head to New York City and one to Washington D.C. on a bombing suicide mission. Because the Enola Gay dropped one of the two atomic bombs and help bring the end of WW II, the mission never materialized.

According to the story about this airplane, there was actually a mission in play to attack the Gatun Lock, at the Panama Canal, that ended when the Japanese surrendered.

Sounded like a good story to me.

https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/aichi-m6a1-seiran-clear-sky-storm/nasm_A19630308000

The story goes: The actual Japanese pilot of the plane ( this had to be like 4th hand) saw this airplane at the Air and Space Museum and said the Enola Gay saved his life, there was a mission where a Japanese submarine armed with 2 of these airplanes sealed in a watertight bay would make its way to the United States eastern coast, where the 2 planes would launch, one would head to New York City and one to Washington D.C. on a bombing suicide mission. Because the Enola Gay dropped one of the two atomic bombs and help bring the end of WW II, the mission never materialized.

According to the story about this airplane, there was actually a mission in play to attack the Gatun Lock, at the Panama Canal, that ended when the Japanese surrendered.

Sounded like a good story to me.